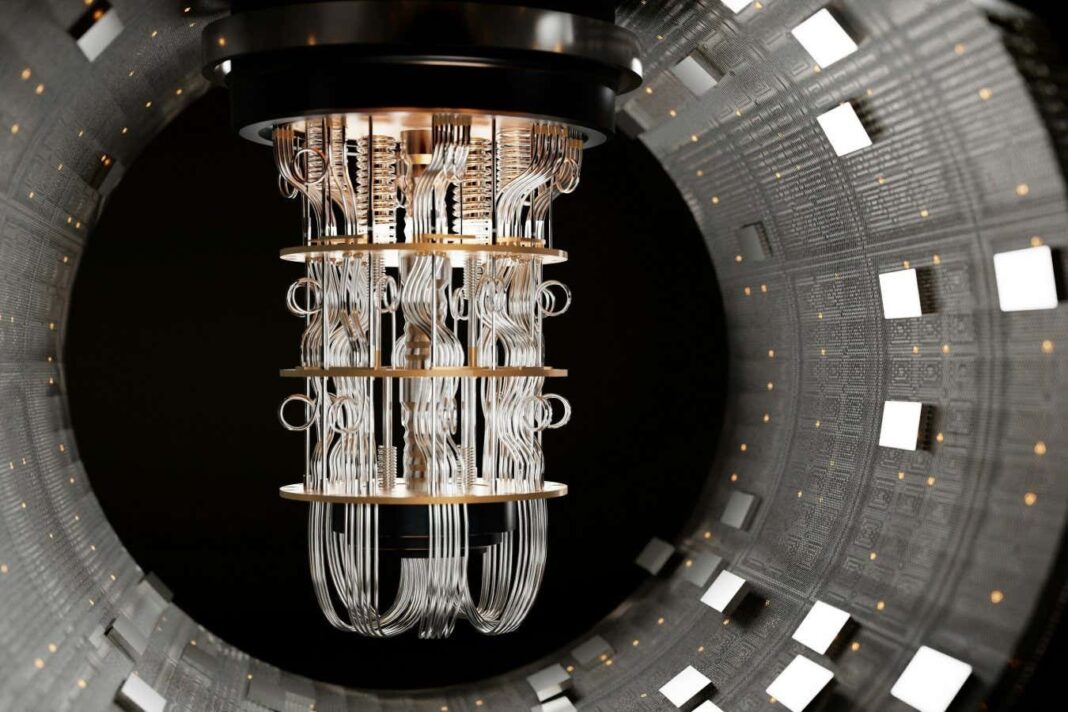

Quantum computing has transitioned from theoretical promise to practical utility faster than many anticipated, marking a significant shift in scientific capabilities by late 2025. After years of development, these machines are no longer just demonstrating quantum phenomena; they are actively being used to simulate and explore complex systems previously inaccessible to traditional computers.

From Feynman’s Vision to Real-World Simulations

The foundation for this progress dates back to Richard Feynman’s 1981 observation that simulating nature effectively requires a system built on quantum mechanical principles. Today, companies like Google and IBM, alongside numerous academic institutions, have realized this vision. Their devices are now capable of simulating reality at the quantum level, yielding insights across multiple fields.

High-Energy Physics and Quantum Fields

Early breakthroughs in 2025 came from high-energy particle physics. Two independent research teams utilized Google’s Sycamore chip (superconducting circuits) and QuEra’s chip (cold atoms) to simulate the behavior of particles in quantum fields. These simulations, while simplified, provide a new way to analyze particle dynamics—a critical step toward understanding complex interactions within particle colliders. The ability to model these fields, which govern how forces act on particles, is particularly valuable because classical simulations struggle with the time-dependent nature of particle behavior.

Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science

The utility of quantum computers extended into condensed matter physics, a field crucial for semiconductor technology. Researchers at Harvard and the Technical University of Munich simulated exotic phases of matter predicted theoretically but difficult to observe experimentally. This marks a turning point; quantum computers are now predicting material properties where traditional methods fall short. The implications are substantial, potentially accelerating the development of new materials with tailored properties.

Practical Applications in Chemistry and Beyond

Google’s Willow superconducting quantum computer was leveraged to run algorithms for interpreting Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy data, a standard technique in biochemical research. While current demonstrations don’t surpass classical computers, the underlying mathematics suggests quantum algorithms could eventually unlock unprecedented molecular detail. The pace of hardware improvement will determine when this potential is realized.

Superconductivity and Metamaterials

Further advancements included simulations of superconductivity using Quantinuum’s Helios-1 trapped ion computer. Modeling materials with zero electrical resistance is vital for efficient electronics and sustainable energy grids, but practical superconductors remain elusive. Quantum simulations of key mathematical models could accelerate the discovery of materials with these properties. Similarly, IBM quantum computers simulated metamaterials—engineered materials with unique properties—potentially advancing research into catalysts, batteries, and light-to-electricity converters.

Exploring Extreme Physics: Neutron Stars and Early Universe

The University of Maryland and University of Waterloo used a trapped ion quantum computer to model the strong nuclear force, a fundamental interaction governing matter at extreme densities. This research, though approximate, provides new insights into neutron stars and the early universe, where these forces dominate.

The Ongoing Race: Benchmarking and Quantum Advantage

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Quantum computers are still error-prone, requiring post-processing to mitigate inaccuracies. Benchmarking against classical computers is also complex, as traditional methods continue to improve rapidly. IBM’s new “quantum advantage tracker” aims to provide a transparent leaderboard of where quantum computers outperform classical machines.

Conclusion

The past year has demonstrated that quantum computers are no longer just theoretical tools but active participants in scientific discovery. While caveats and approximations persist, the shift is undeniable: these machines are now enabling research previously impossible, marking a significant leap forward in our ability to simulate and understand the universe. The pace of progress suggests that 2026 could bring even more quantum surprises.