Recent research suggests sea turtles may be better equipped to handle rising global temperatures than previously feared. While concerns about skewed sex ratios – with warmer nests producing overwhelmingly female hatchlings – have been widespread, new findings reveal a surprising genetic flexibility that could help these reptiles maintain a more balanced population structure even as the climate warms.

The Temperature-Sex Paradox

For sea turtles, unlike humans and many other animals, sex isn’t determined by chromosomes but by nest temperature. Higher temperatures yield females, while lower temperatures produce males. This has led to alarming projections, such as the 2018 study finding that 99% of young green turtles from warmer nesting sites in Australia were female. Without enough males, populations were expected to collapse.

However, accurately assessing hatchling sex in the wild has been nearly impossible until now: determining a turtle’s sex requires invasive procedures. To bypass this limitation, researchers led by Chris Eizaguirre at Queen Mary University of London conducted controlled experiments with loggerhead turtles.

Genetic Mechanisms at Play

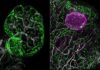

The team incubated eggs at varying temperatures (male-promoting, pivotal, and female-promoting) and then used genetic analysis to determine sex via blood samples before definitive physical characteristics developed. They discovered that regardless of incubation temperature, males and females exhibited distinct patterns in gene activity due to a process called DNA methylation – an epigenetic change influencing how genes express themselves.

Specifically, hundreds of genes showed altered activity: 383 were suppressed in females and 394 in males. These genes are known to play roles in sex development, allowing researchers to predict sex with high accuracy from a simple blood sample.

Field Data Confirms Resilience

To validate these findings in the real world, the team tracked loggerhead nests on Sal Island in Cape Verde, burying eggs at different depths to create warmer and cooler microclimates. Sequencing hatchling blood samples revealed a surprising outcome: far more males hatched than predicted based on temperature alone. Models overestimated female production by 50-60%.

This suggests turtles possess molecular mechanisms that help them adjust to changing conditions by modifying how sensitive their sex development is to temperature. “We are not saying that there is no feminisation because there is, and we’re not saying that climate change does not exist because it is there and it’s accelerating,” explains Eizaguirre. “What we are saying is that when the populations are large enough, when there is sufficient diversity, then it looks like the species [can] evolve in response to the climate they live in.”

Beyond Genetics: Behavioral Adaptations

Other research corroborates these findings. Studies by Graeme Hays at Deakin University show more male turtles hatching than expected if temperature were the sole determinant. Additionally, turtles exhibit behavioral adaptations, such as nesting earlier in the year and migration patterns that reduce feminisation impacts. Male turtles also travel to breeding grounds more often than females, balancing the breeding sex ratio.

While hatchlings still face heat stress, leaving lasting DNA methylation changes, the observed molecular adaptations provide encouraging news for these vulnerable reptiles.

The combination of genetic flexibility and behavioral adjustments suggests sea turtles may be more resilient to climate change than previously thought, though continued warming remains a significant threat.