For years, explosive crackdowns have punctuated the growth of illicit scam operations across Southeast Asia. The demolition of KK Park in Myanmar – a notorious “scam center” housing tens of thousands of people forced into fraud – was presented as a victory. Yet, the operators vanished before the bombs fell, relocating while leaving behind thousands of likely trafficked victims. This pattern is not an exception, but the norm: a calculated evasion illustrating a deeper problem.

Experts now describe the region as entering an era of the “scam state” – countries where large-scale fraud has become deeply integrated into institutions, economies, and even governments. The industry has grown so massive that it rivals the global drug trade in scale, generating tens of billions of dollars annually. Unlike traditional organized crime, these operations aren’t hidden: they operate openly, often with impunity.

The Industrialization of Fraud

What began as small-scale online scams has mutated into a highly organized, industrial political economy. In the past five years, scamming has become a dominant economic force in the Mekong sub-region, driving corruption and reshaping governance. Despite official denials, governments in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos have shown little genuine interest in eliminating an industry that fuels their economies. Crackdowns are often described as “Whack-a-Mole” tactics: performative actions that target minor players while leaving the core networks intact.

The core of this illicit economy lies in “pig-butchering” scams, where victims are groomed in online relationships before being defrauded of staggering sums. Sophisticated technology, including generative AI, deepfakes, and cloned websites, now drives these operations. Victims report losing an average of $155,000 each, often over half of their net worth.

State Complicity and Economic Reliance

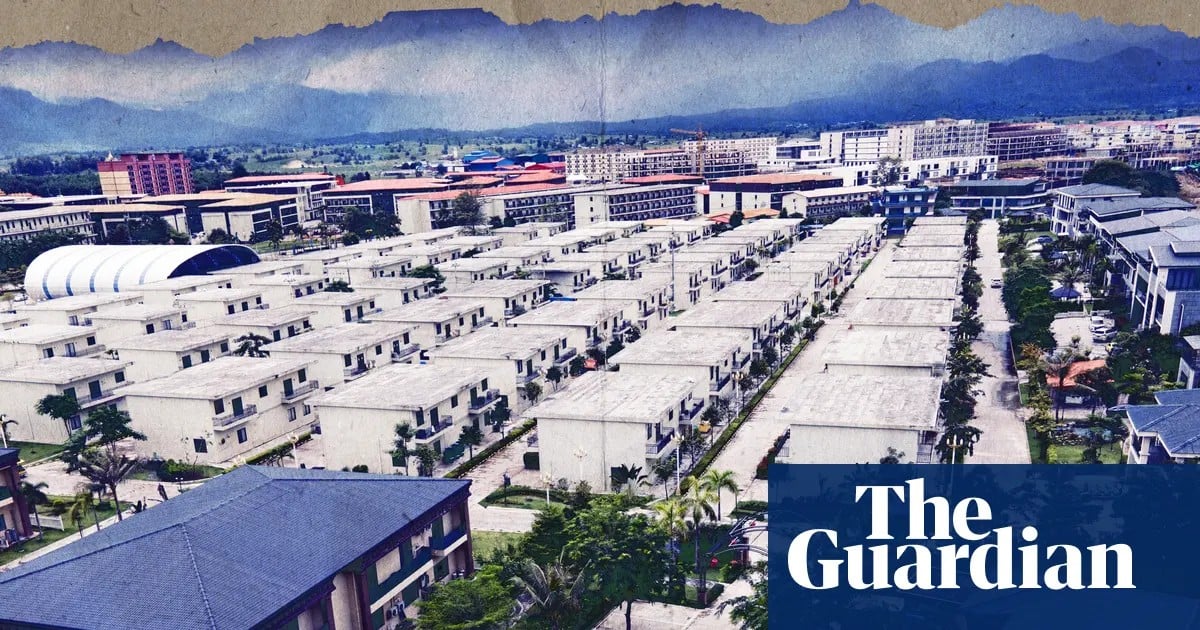

The scale of the industry is staggering: estimates range from $70 billion to hundreds of billions annually. This has led to a rapid build-up of infrastructure in conflict zones and lawless border areas. In Laos, around 400 scam compounds operate in special economic zones. In Cambodia, one company allegedly targeted $15 billion in cryptocurrency – an amount equal to half of Cambodia’s entire economy.

This isn’t just about money; it’s about political and state-level involvement. Scam masterminds are operating at high levels, securing diplomatic credentials and acting as government advisors. In Myanmar, scam centers have become a key financial flow for armed groups. In the Philippines, ex-mayor Alice Guo was recently sentenced to life in prison for running a massive scam operation while in office.

The New Normal

The blatant impunity is itself telling. These compounds are built in public view, with states tolerating or even enabling the criminal activity. This level of state co-optation is unprecedented in modern illicit markets. The situation is escalating rapidly, with the scam economy doubling in size since 2020.

“This is a massive growth area… This has become a global illicit market only since 2021 – and we’re now talking about a $70bn-plus-per-year illicit market.” – Jason Tower, Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime.

The rise of “scam states” represents a new era in transnational crime, one where corruption, economic dependence, and political impunity converge to create a self-sustaining, multi-billion-dollar ecosystem. The problem isn’t just about fraud; it’s about the erosion of governance and the normalization of state-sponsored criminality.