Archaeological discoveries in South Africa have pushed back the timeline for poisoned weaponry, proving humans used toxic arrowheads at least 60,000 years ago – significantly earlier than previously believed. Researchers at the University of Johannesburg and Stockholm University, among others, have identified traces of potent plant alkaloids on ancient stone arrowheads excavated from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter in KwaZulu-Natal.

The Evidence: Ancient Toxins Preserved

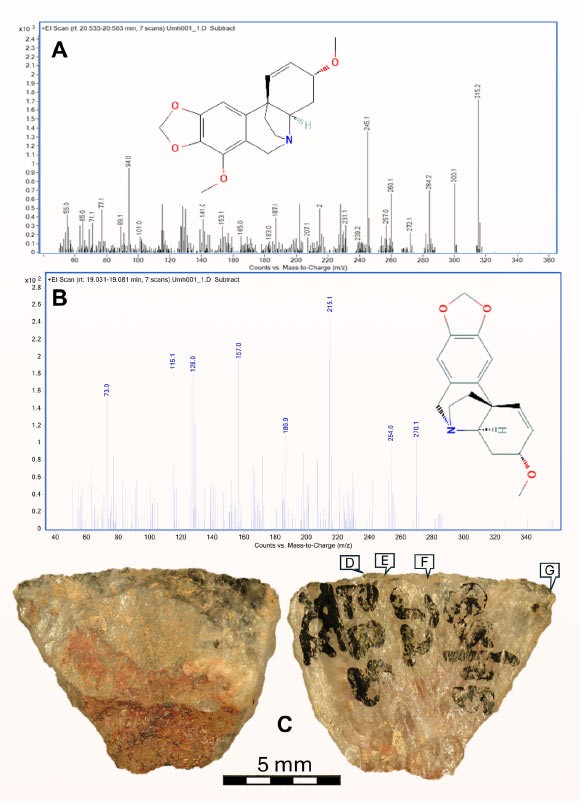

The artifacts, known as backed microliths, contained residues of buphandrine and epibuphanisine, toxins exclusive to plants in the Amaryllidaceae family native to southern Africa. The most likely source of these poisons is Boophone disticha, a species historically used for arrow poisons. Analysis via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry confirmed the presence of these compounds on five out of ten microliths examined.

Notably, visible residue patterns suggest that early humans carefully mixed these toxins into adhesives used to attach the stone tips to arrow shafts. Microscopic examination of the arrowheads revealed wear consistent with transverse hafting – a method for securely attaching the point to the arrow.

Why This Matters: Rethinking Early Human Capabilities

This discovery dramatically changes our understanding of early human hunting strategies and cognitive abilities. Before this, the oldest confirmed use of arrow poison dated back several thousand years. The Umhlatuzana findings prove that sophisticated, chemically-informed hunting techniques were in use during the Late Pleistocene.

This isn’t just about tools; it’s about planning and understanding cause-and-effect. Using poisons isn’t instant death; these toxins likely weakened prey over time, allowing hunters to track them. This implies advanced knowledge of animal behavior and plant chemistry.

Connecting the Past and Present

Researchers validated their findings by comparing ancient residues with poisons extracted from historical arrowheads collected in South Africa during the 18th century. The chemical stability of these substances allowed for preservation over tens of thousands of years, providing a direct link between prehistoric and historical practices.

“Finding traces of the same poison on both prehistoric and historical arrowheads was crucial,” said Stockholm University’s Professor Sven Isaksson. “By carefully studying the chemical structure of the substances, we were able to determine that these particular substances are stable enough to survive this long in the ground.”

The study, published January 7 in Science Advances, underscores that early humans were not only capable of inventing advanced tools like the bow and arrow but also possessed a deep understanding of natural chemistry to improve their hunting efficiency. This discovery reinforces the idea that early human ingenuity was far more complex than previously assumed.

Ultimately, these findings highlight the critical role of chemical knowledge in early human survival. The ability to harness toxins for hunting represents a significant cognitive leap, demonstrating a level of strategic thinking previously underestimated in ancient populations.